It was late in 2014 – and a scenario many business families fear.

Samsung chairman Lee Kun-hee, the 72-year-old son of the company’s founder, had suffered a heart attack, leaving the family scrambling to address a leadership transition far sooner than expected.

One of the world’s largest companies – a $400 billion conglomerate including not just smartphones and electronics, but also shipbuilding, hotels and resorts, construction, advertising and even life insurance – suddenly faced questions about who would take over, steady the ship, and lead the company forward.

And this was no normal business family transition.

The Lee family would need to navigate its leadership change delicately. South Korean tradition dictates that no heir can take over the business until the patriarch has died. The problem? Kun-hee wasn’t dead, but his health problems left him incapacitated and unable to lead the company.

So slowly, re-writing the script as they went, the Lee family transitioned increased responsibilities to Kun-hee’s only son, Lee Jae-yong, who was appointed Vice Chairman of Samsung Electronics.

But that issue would soon pale in comparison to what came next.

Espionage, bribery, succession battles, and sibling rivalries — these are ingredients of the real-life drama of the Lee family, now in its third generation of leadership as an international business juggernaut.

Succession in business families is challenging enough on its own. But what kind of company survives this much upheaval and uncertainty? And how does such a company recover and look to the future?

First, the backstory.

Samsung was started by Lee Kun-hee’s father, Lee Byung-chul, as a dried foods export business in 1938. Legend has it that Byung-chul had only $25 in his pockets to start the business, using these few dollars to establish a tiny store that exported mainly fruit and fish. He named the business Samsung, which means “three stars” – three being a lucky number in South Korea, with the stars meant to signify that the company would be powerful and everlasting.

Whether it was luck or tenacity, Lee Byung-chul’s business quickly flourished. By the mid-1950s – after the Korean War – the company partnered with the government to drive economic development, expanding into electronics, shipbuilding, petrochemicals, heavy machinery, and construction. Who knew then that Samsung would, decades later, launch one of the most coveted smartphones, the Galaxy S, on the market?

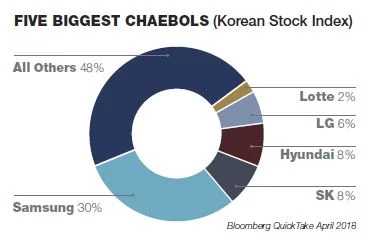

Today, Samsung is the largest conglomerate in South Korea.

More specifically, its group of companies is known as a chaebol in South Korea – owned by a de facto holding company, Cheil Industries.

Until recently, over 60 of Samsung’s affiliates were organized into a complex cross-shareholder structure. This has enabled the Lee family to retain control over the companies while owning just a small percentage of their shares.

Samsung’s chaebol now spans electronics, life insurance, fashion, and hospitality. Samsung Heavy Industries manufactures ships and oil platforms, while another affiliate, Samsung Everland, operates the largest amusement park in South Korea. Samsung also has interests in financial services: investing, credit cards, and venture capital. All told, the empire accounts for an estimated 15% of South Korea’s GDP. The market cap of Samsung Electronics alone ws US$325.9 billion in 2018, making it Forbes’ 14th largest publicly traded company in the world.

Samsung Electronics accounts for about two-thirds of the total value of the chaebol.

Throughout this history of expansion, growth, and constant change, Samsung – and the Lee family – has also faced its fair share of ups and downs, its own twists and turns.

STOPS AND START IN THE FAMILY SUCCESSION

Lee Byung-chul had three sons among his eight or nine (never really verified) children. This would seem to set Byung-chul up for an orderly succession, but he was forced to step down in 1966 when his second-eldest son, Lee Change-hee, was charged with smuggling 50 tonnes of saccharin, an artificial sweetener, into South Korea. Following South Korean tradition, the eldest son, Lee Maeng-hee, took over.

But Maeng-hee’s leadership tenure was short-lived. His was an aggressive leadership style, he was disliked by his father’s closest allies, and he managed to drive the company into chaos in six brief months. Lee Byung-chul resumed control not long after.

A few years later, Lee Byung-chul’s second son also made a run at the company – by telling the president of South Korea about a slush fund kept by his father. So, by 1969, both Lee’s first and second sons were written out of the line of succession in the company, leaving it to his third son, Lee Kun-hee, to take over when Byung-chul died in 1987.

It wasn’t all smooth sailing for the unintended heir. Many people believed Lee Kun-hee was a playboy, and unprepared for the job. But armed with an economics degree and an MBA from George Washington University, he set about turning Samsung into a premium brand.

The chaebol under Chairman Lee Kun-hee invested heavily in research and development, but didn’t seek to be an innovator. Its strategy instead was to be a “fast follower” – creating high-quality, efficient iterations of others’ products, moving them to market quickly, and reaping the benefits of fast growth.

ON TO THE THIRD GENERATION

Lee Kun-hee would oversee a growing and powerful Samsung for more than 35 years. It’s one reason why his heart attack in 2014, and his resulting incapacitation at a relatively young 72, was such a jolt to the Lee family. The family now needed to address its succession plan far earlier than anticipated.

The initial challenge for the family was in retaining control and stability during this early transition to the third generation. Lee Kun-hee had four children – three daughters and his only son, Lee Jae-yong. Today, the two daughters occupy senior positions in the company. Lee Boo-jin runs Hotel Shilla and the family’s hospitality interests while Lee Seo-hyun is responsible for Samsung’s advertising and fashion businesses. The two women are also co-presidents of Cheil Industries. Their youngest sister committed suicide in 2005.

This brings us back to Lee Jae-yong, the only heir (as the only son) to the family’s business throne, according to South Korean tradition. He became vice chairman of Samsung Electronics in 2014, at the time of his father’s heart attack and incapacitation. Two years later, he joined the Board.

Even though tradition dictates Jae-yong won’t (officially) take over until his father dies, the practicality is another matter. Today, Kun-hee lives on and Jae-yong is considered to be in charge. In early 2018 the Seoul High Court called him the de facto head of Samsung Group, and the Korea Fair Trade Commission gave him the same designation a few months later.

TIGHTENING REGULATIONS – AND A HEFTY INHERITANCE TAX

Kun-hee’s health troubles also came at a time of increasing public pressure on the chaebols in South Korea. These huge family-run businesses had come to be perceived as too close to the government. Around the same time, the South Korean government banned the use of cross-shareholdings and offered tax incentives to companies that restructured – all in the interests of improving transparency and corporate governance in family-run chaebols. But, adding to the tension and complexity, President Park Geun Hye’s government was felled when Park herself was accused of working too closely with certain chaebols, including Samsung. Park was sentenced to 24 years in jail for corruption and bribery in the spring of 2018.

Since then, the new government in South Korea, led by leftist Moon Jae-in, has gained popularity for its tough stance on the chaebols. Moon’s government includes many critics who want more control for shareholders and less for the large business families. As a result, these emerging government regulations are now forcing Samsung to unsnarl its convoluted ownership structure.

Lee Jae-yong had already signalled plans to simplify the ownership structure of the Samsung Group. Specifically, he plans to make each affiliate more venture-like and independent. This will improve transparency and could lead to a clearer holding company arrangement.

Another issue complicating the transition is a hefty inheritance tax. The bill for the transfer of Chairman Lee’s shares in just three companies — 3.4% in Samsung Electronics, 20.8% in Samsung Life and 1.4% in Samsung C&T Corp. – could leave his children liable for more than $6 billion. The complex ownership arrangement once meant that shares within the Samsung Group traded at a discount. And now, the higher share prices climb, the greater the inheritance tax bill. (Be careful what you wish for.)

Consequently, it’s now anticipated that Jae-yong will sell his father’s shares in certain Samsung affiliates in order to foot the bill. And some Samsung affiliates have already been made public. Cheil Industries went public in 2014 with a $1.4 billion initial public offering. Samsung SDS, a technology provider for the construction and manufacturing industries, went public in 2014 raising $5 billion for the Lee heirs. Samsung has also sold its holdings in several defense and chemical affiliates.

All in preparation for a whopping inheritance tax.

And that’s not the only challenge for the Lee family.

LEGAL TROUBLES FOR THE HEIR

In early 2017 – barely two years into his unofficial duties as head of Samsung – Jae-yong was charged with bribing President Park and one of her advisors. Among other charges, prosecutors argued that Jae-yong and other Samsung executives offered incentives to the president and her close friend to allow a merger between two Samsung affiliates. The proposed deal would have secured the Lee family’s control over the empire – and, speculation has it, also helped to finance the looming inheritance tax.

Part of the alleged bribe came in the form of an $800,000 thoroughbred show horse, gifted to the daughter of President’s Park’s friend, who was an Olympic equestrian. Samsung was also charged with making payments of up to $37 million to organizations linked to President’s Park’s friend. Jae-yong and his executives denied the gifts were bribes, characterizing them instead as normal support for the South Korea’s Olympic team.

The allegations created a media firestorm, captivating South Korea. It was opposite to what Samsung and the Lee family needed in those fragile months after Lee Kun-hee’s heart attack.

After what was called the ‘trial of the century,’ Jae-yong was found guilty on charges of bribery, embezzlement, and perjury – and sentenced to five years in jail. But after serving less than a year, he was released on appeal, with a reduced and suspended sentence. The High Court ruled that Samsung was coerced by the former president to make certain contributions.

Jae-yong is now appealing the rest of the charges to the Supreme Court.

Meanwhile, the share price of Samsung Electronics hasn’t been hurt by the scandal. It was only during the summer of 2018, almost six months after Jae-yong was released, that share prices fell, due instead to slowing smartphone sales.

RECOVERY AND AMBITION

Meanwhile, Jae-yong and Samsung have lofty goals for the next few years.

The chaebol hopes to compete with the likes of Google and Amazon in software, with a promise to equip all appliances with artificial intelligence technology and internet connectivity by 2020. In addition, Jae-yong is making innovation a priority: Samsung recently announced plans to spend $22 billion on auto technology, artificial intelligence, and 5G wireless in the next three years, creating 40,000 new jobs.

Jae-yong also plans to further detangle the family’s convoluted ownership structure. Two affiliates will sell off their shares in Samsung’s holding company, removing the last four examples of circular shareholding in the conglomerate. This will mean that Jae-yong will enjoy less control than his father ever did. Even so, the Lee family is expected to retain its significant stake in Samsung Electronics.

Jae-yong’s recent legal challenges, his father’s incapacitation, and Samsung’s plans for the future are just the beginning of a fragile transition period for the Lee family. Jae-yong continues to grapple with pressures from both the South Korean government and the country’s society to make Samsung more transparent and accountable. And all the while he must ensure that Samsung remains competitive across its businesses and industries.

How the Lee family continues to manage these challenges and secure Jae-yong’s role as the third-generation heir will offer lessons for family businesses around the world.

Questions to consider for your business:

- Are you prepared for a succession that happens earlier than you anticipate?

- Are you meeting or exceeding corporate governance and transparency requirements?

- Do you have a ‘liquidity plan’ to help finance potentially large tax liabilities as you transition the business to future generations?

Sarah Reid is a Toronto freelance writer.